As

director of aural skills courses, I soon became

aware of the importance of the harmonic dimension to the study of tonal

music. The tonal system is, in fact, defined specifically and primarily

by the harmonic dimension, but it is this very aspect has always

proved to be the most disheartening for students because it is the most

difficult to

circumscribe. The constraints imposed by this type of formation, which

is rooted in reading and listening, made it necessary for me to maintain

a

constant preoccupation with the relationship between what we hear and

what we see. With this in mind, I had to search beyond (or beneath!)

the procedures of musical analysis such as, for example,

Schenkerian or

semiological systems. We know very well

that, it is only at the end of a long and

meticulous re-writing process that we can attain the Schenkerian objective, and in the same way, the semiological perspective demands, when analysing a text, a process of microscopic

dismantling that is incompatible with our goal of maintaining a strong

reference to the auditive data.

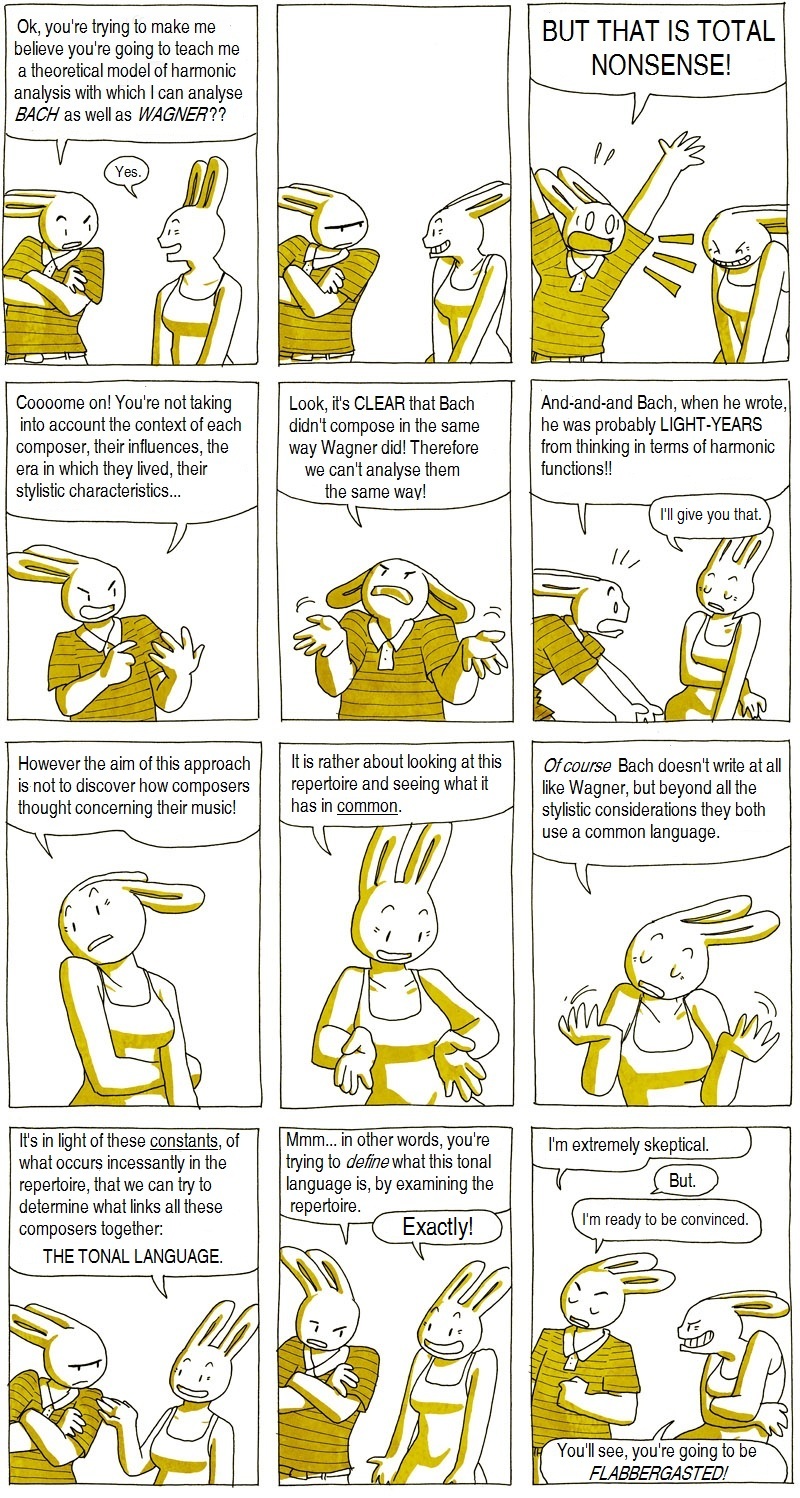

Thus,

the challenge for me was this: to find or create tools that can help

students who are faced with the complexities of harmonic listening

(tonal harmony in this case). Was there a way to extract the basic principles of an harmonic practice common to composers from Bach

to Wagner

by identifying their preferred habits and thus constants that could be

defined with

enough precision that they could serve as the foundation for both an

aural and visual formation in this language? Such a perspective, however,

led me to exclude

all historical contexts or circumstances, as well as all stylistic

considerations concerning each and every one of these tonal works which

contribute to a single, immense corpus.